A new year is here, and it’s time to tally up the animals we’ve lost. During 2017, at least seven species went extinct in the wild. Wildlife ecologist and conservation biologist David Steen calls us to witness their loss:

“Human beings are one of the species on Earth. That does not mean that anything and everything we do is natural and therefore okay, even if it means causing species to go extinct,” wrote Steen. “Other species have value and we should act accordingly to keep them around.”

Steen has been assembling lists of species that go extinct in their natural habitats since 2012. Although some of the animals on the list still exist in zoos or captivity, they can’t be found in the wild anymore.

1. Fishing Cat: Extinct in Indonesia

The fishing cat is found in many parts of Asia, so it isn’t completely “extinct.” However, its Indonesian population hasn’t been seen in a while, leading many to believe it has been wiped out.

“This is sad news, but we hope that we are proved wrong and the fishing cat is rediscovered on Java,” a representative of the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund Nevertheless Frederic Launay told the National Geographic. “Nevertheless, fishing cats still exist across a wide range and our focus should be on assessing population health and reducing threats elsewhere.”

Even in the places the fishing cat still exists, the outlook isn’t good. The species is considered vulnerable, but while a vulnerable classification should – in theory – trigger higher levels of protection for a species, there’s rarely enough political will to stop threats to an endangered animal. The fishing cat’s habitats are being destroyed by humans and replaced by farms, communities, and industry. On top of that, the fishing cat is poached for its fur.

2. Beaverpond Marstonia: Extinct

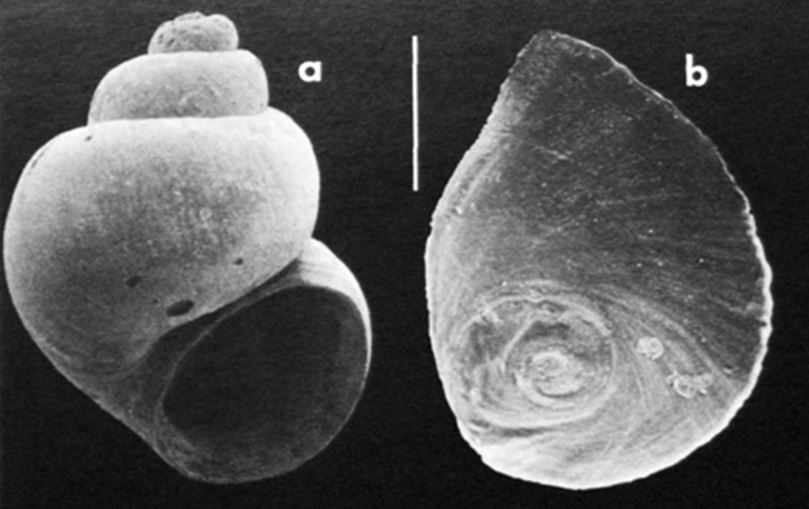

Picture of newly extinct Beaverpond Marstonia (Marstonia castor) by Hershler/Smithsonian.

It might be small, and only found in the U.S. state of Georgia, but this little snail played a part in its ecosystem and enriched biodiversity. Unfortunately, this species is likely gone for good. Overdevelopment and the reallocation of water has led to its decline. It hasn’t been spotted since 2010, leading the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to declare in 2017 that the beaverpond marstonia is now extinct.

“It’s heartbreaking to lose wildlife to extinction, especially when timely intervention could have saved the species,” said senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, Tierra Curry. “The loss of the beaverpond marstonia is yet another wake-up call to the Fish and Wildlife Service that urgent action is needed to prevent the extinction of more Southeast species.”

3. Christmas Island Pipistrelle: Extinct

The Christmas Island Pipistrelle is one of a few species that went extinct in Australia last year.

Christmas Island in Australia is home to a number of unique species, but more and more of them are dying out, including a tiny bat called a pipistrelle. Although none of these bats have been seen since 2009, it wasn’t officially listed as extinct until 2017, when the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) updated its status.

“What is clear is that stemming the global loss of biodiversity through recovery planning will require brave, effective governance, leadership and decision making in the face of uncertainty,” urged Tara Martin. Martin cowrote an article analyzing how Australian institutions are failing endangered species.

The overdue updating of the IUCN status list is a good example of the current government’s distaste for taking action. Monitoring the steady decline and disappearance of our threatened species is not good enough. Martin concludes that “monitoring must be linked to decisions, institutions must be accountable for these decisions and decisions to act must be made before critical opportunities, and species, are lost forever.”

The bat’s extinction marked the first time in 50 years a mammal had gone extinct in Australia. Sadly, it wasn’t the last. Two other species found only on Christmas Island also went extinct this year.

4. Christmas Island’s Lister’s Gecko: Extinct in the wild

Lister’s Gecko has been struggling in the wild for a long time. The gecko used to be common, but in 1982, Wolf Snakes were brought to the island and preyed on the gecko, bringing it to the brink of extinction. Fresh hope came in 2009 when a small surviving population was found in the wild. Most of these geckos were taken into captivity to give the species a second chance, or as it turned out, a safety net. The last time Lister’s Gecko was seen in nature was in 2012. Now, the IUCN has acknowledged its extinction in the wild. The captive population is still growing, offering some hope that it may one day be released to a safer home.

5. Christmas Island Forest Skink: Extinct

Picture of the newly extinct Christmas Island Forest Skink by Bernard Dupont, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Just like the Lister’s Gecko, the Forest Skink was facing a losing battle against the introduced Wolf Snake. But there were other villains in this story: an invasive species of ants called Yellow Crazy Ants are a threat to many endangered species on Christmas Island. By 2011, no Forest Skinks were left in the wild. In 2014, the last Forest Skink, affectionately named Gump, died in captivity. The species wasn’t officially recognised as extinct until 2017.

6. Christmas Island Blue Tailed Skink: Extinct in the wild

Cryptoblepharus egeriae, the Blue Tailed Skink from Australia’s Christmas Island has gone extinct in the wild.

The Blue-tailed Skink suffered a similar fate to the Forest Skink and Lister’s Gecko. Its remaining population was pulled from Christmas Island in 2009 to breed in captivity, where it is recovering. The IUCN reviewed the species last year and changed its status to extinct in the wild.

7. Stichocotyle nephropis: Extinct

The final species named extinct in 2017 was a marine parasite found in Scotland. The last sighting of the species was in 1986. A paper published last year argues the parasite has gone extinct: not only has it been 31 years since it’s been seen, but the fish it usually lives within are listed as threatened or endangered from overfishing. With so few hosts, it’s unlikely the parasite has survived.

Sadly, even more animals are likely to become extinct in the near future. Scientists predict that by 2100, half of the earth’s species will become extinct. Losing each and every one of these, however small, has repercussions on earth’s ecosystems. Some even say the earth is experiencing its sixth mass extinction. Unlike other mass extinctions, though, human actions are causing this one. And unlike the earlier mass extinctions, humans can do something about it. To save the threatened species that remain in the wild, the people who love them will have to fight for brave and effective policies that demand action, not a body count.