On the morning of May 12, 2021, researchers at the University of Minnesota put a 1-year-old tuxedo kitten named Tammy under anesthesia so they could drill a hole through her skull and implant an electrode in her brain.

Tammy, who also was known by the numbers tattooed in black ink inside her ears, had undergone anesthesia for procedures at least 15 times — starting when she was a 10-week-old kitten — according to documents obtained by Lady Freethinker through a public records request.

Researchers had noted she didn’t recover well, with historically prolonged recoveries, hypothermia (dangerously low body temperatures), vomiting, weak muscle control, coughing, bruises, and a lack of appetite for days. Once, she had lost 12 percent of her body weight. Another time, when she became hypothermic, researchers took nearly a half hour to get her back into the safe zone.

But they kept using her.

On the Wednesday morning of her scheduled skull drilling, Tammy tried to hold out — but her small body had had enough.

At 11:32 a.m. — after researchers had blown a vein, tried for 17 minutes to intubate her, let her body temperature drop dangerously, and attempted CPR when her heart stopped — Tammy died. Seven minutes later, her corpse was in a bag and on its way to a “carcass cooler,” according to her monitoring records.

Tammy was just one of at least 40 kittens undergoing brutal experiments at the university’s Minneapolis site. But she wasn’t the only kitten to die in 2021.

April, a 3-month-old kitten, was killed after a researcher gave her nearly five times the approved dose of the paralytic vecuronium — in alleged violation of the federal Animal Welfare Act, according to an official warning from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) — and she struggled to breathe and likely suffered organ damage.

Researchers also killed Casey, an 11-week-old kitten whose tongue turned blue following repeated intubation attempts during one brain scan and who had six veins blown on the day he died.

Protocol documents, obtained by Lady Freethinker (LFT) through a public records request and public records portal NIH RePORTER, indicated researchers were attempting to “push the technology envelope” and “lead to transformative breakthroughs in understanding dynamic functions of the human brain” by manipulating the brains of 8- to 10-week-old kittens with electric pulses, light rays, and visual stimuli. They then reportedly wanted to study the results at the laminar and columnar levels using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).

Although the protocol notes the study is terminal — meaning researchers planned to kill all the kittens going in, specifically so they could collect their tissues — monitoring records obtained by LFT through a public records request show that kittens also died suddenly or suffered, sometimes for days, before researchers chose to “euthanize” them — with unintended repercussions including inflamed tracheas, strained breathing, vomiting, hypothermia, bruises, punctured and blown veins, and a seizure.

At least four kittens died or were euthanized in 2021 alone due to unanticipated complications or poor likelihood of recovery, according to the records.

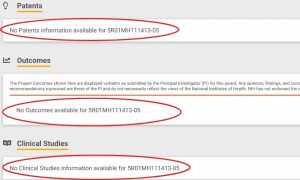

The study, although consuming years of precious research time and over $9 million of taxpayer-supported funding through the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH), has not yielded any direct clinical applications for humans — or cats — to date.

The experiments also were suspended following the warning from the USDA, according to the university.

The University of Minnesota said in a statement to Lady Freethinker that it is “as serious about maintaining the highest standards of humane care and use of animals as it is about its mission of advancing knowledge and improving health” and that its animal care use committee “reviews all projects involving animals to ensure that scientific rationale is provided, alternatives have been considered, and refinements are made to minimize pain and distress.”

“While the University of Minnesota regrets what happened in this case, these are rare instances that represent a handful of the approximately 1,000 animal-related research protocols active each year at the U of M,” the statement said. “The incidents referenced here have been previously reported to University officials and shared by the U of M with the appropriate federal agencies as part of its commitment to robust self-reporting.”

The university did not offer any evidence about any clinical applications relevant to human health from the kitten experiments to date. The public relations office also told LFT that — despite the cited review and approval — the protocol involving the kittens was suspended and the lab was “required to create and refine an entirely new protocol.”

That new protocol has been approved, but researchers have not yet picked back up the experiments, the university said.

NIMH did not respond to media inquiries.

(Source: NIH RePORTER. Emphasis: Lady Freethinker)

Deadly Experiments on Kittens

According to public records documents, university researchers told the NIMH and their animal care use committee they wanted to study how inhibiting or stimulating neural activity in certain parts of the brain could impact brain function, connectivity, and circuitry.

They planned to anesthetize and temporarily paralyze several groups of 8- to 10-week-old kittens — who at that young age would be small enough to fit into their scanners — acquired from Liberty Research, Inc, or recycled from other experiments.

One group of paralyzed kittens would be presented with visual stimuli — with monitoring records for one kitten referencing a “vedio [sic] of cat/mice” — while undergoing fMRI scans.

Several other groups of kittens would undergo craniotomies — surgical procedures in which researchers would use a high-powered drill to bore a 6-10 mm hole in the skull – to implant electrodes or probes, which would be held in place with “dental cement or superglue.”

Researchers would then “stimulate” the kittens by jolting them with “a very small electric current” or sending light rays through the implanted devices, while using fMRI to scan for changes in the kittens’ brains, according to the protocol document.

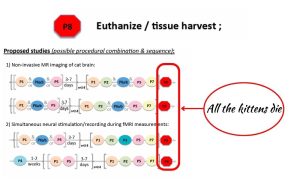

Some of the kittens undergoing craniotomies would be killed following the procedure. Others would be kept alive for additional tests before they, too, would be killed.

(Document: University of Minnesota. Emphasis: Lady Freethinker)

Preparation for the hours-long scans and craniotomies also involved additional invasive procedures, including blood draws, intubation, and intravenous catheters inserted through incisions in the kittens’ legs and tails.

The protocol document also notes that several of the kittens would be used in “training,” with a “higher potential for trauma” and vessel damage during intubation and catheter insertion and a limit of three attempts per session.

Regardless of the group they ended up in, all surviving kittens would ultimately be killed via “euthanasia” drugs, the researchers wrote.

Researchers told the NIMH that cats were “widely used” for brain studies and that there were “no feasible alternatives.” They expected complications to be minimal, noting possible pain, distress, and infection.

But public records documents show numerous complications for kittens who died suddenly or whom researchers ultimately chose to kill to end their unanticipated suffering. Monitoring records point to equipment meant to measure the kittens’ vital signs reportedly and repeatedly not working properly and kittens who sometimes underwent up to five attempts at standard procedures, such as intubation or catheter insertion, over prolonged periods in a single session.

Complications and Kitten Casualties

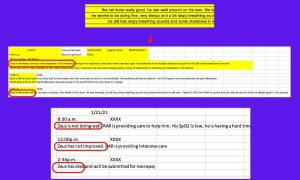

Monitoring records following an fMRI scan for Zeus — a 10-week-old brown tabby kitten also known to researchers as 20KF2 — started out optimistic. After the nearly 5-hour procedure, researchers wrote the kitten “looks really good.”

By the next day, the tone changed. Zeus was not as active as normal. He had an inflamed trachea and raspy, strained breathing. He was spitting up food.

Day 3 brought no improvements. Zeus was “not doing well.” He was cold and struggling to breathe through his still-swollen trachea. Even with intensive care, he died — meaning he suffered for almost two full days after the scan before his body shut down, according to his monitoring records.

Zeus’s monitoring records (Source: University of Minnesota, Emphasis: Lady Freethinker)

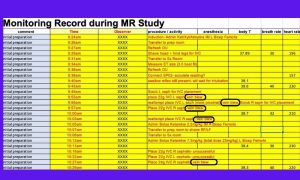

Casey, an 11-week-old kitten also known to researchers as 21DFI#007, also suffered following a standard scan, according to his monitoring records.

Researchers had struggled to intubate him — taking 20 minutes to successfully get the tube down his trachea — and then Casey’s tongue had turned blue. He had low oxygen levels. He was wheezing. Those complications delayed the actual scan until more than three hours into the procedure, after which researchers reported the tiny kitten was “dysphoric” with “vocal, crackly, wheezy respiratory sounds.”

By the evening, Casey was retching, with excessive saliva in his cheeks, according to his monitoring records. Researchers monitored Casey for the next seven days — noting he was lethargic, dehydrated, and continued to have raspy and wheezy breathing.

On the eighth day following the procedure that had resulted in Casey’s complications, researchers put the kitten under anesthesia again for a scheduled skull drilling.

A little after 10 minutes after the procedure’s start, researchers wondered if they were getting accurate oxygen level readings. Then they blew five of Casey’s veins while trying to successfully insert a catheter. They also blew another vein while trying to inject the “euthanasia” drug that would kill the kitten that same day, according to his monitoring records.

Casey’s monitoring records (Source: University of Minnesota. Emphasis: Lady Freethinker)

The handling of another kitten, who had to be euthanized, brought an official warning in October 2021 from the USDA, the federal agency that licenses university laboratories, after a lab member administered a paralytic in 4.5 times the approved dose to the kitten.

“Lab members lacked the proficiency to administer paralytics correctly,” the USDA report notes. “The facility was unable to ensure that all personnel involved with this activity were qualified to perform the procedures resulting in the death of one cat.”

A USDA inspection report referencing a fatal incident on Aug. 5, 2021, and university documents from that same date both point toward the casualty being a friendly 3-month-old kitten named April, also known to researchers as 21DF3#009.

April, whom researchers noted liked “playing and exploring with other kittens” and who “purred when cuddled,” had gone through at least two fMRI scans prior to the fatal procedure — including one in which it took researchers five attempts to successfully intubate her over 44 minutes.

On the day of April’s death, researchers had trouble intubating her again. They noticed irregular ventilation sounds and also indicated at least six times that their equipment to monitor her vitals may not be giving them accurate readings. Monitoring records also indicate a miscalculated anesthesia dosage.

Three hours after starting the procedure, researchers removed April from the scan holder and noted a significant amount of fluid in the endotracheal tube. They wrote that the kitten had “audible lung sounds indicative of pulmonary edema (fluid in the lungs).” A vet called in for assistance suspected likely organ damage and a poor chance of recovery.

April didn’t go back to the live animal room that day. Instead, she went into a body bag and a carcass cooler. In its issued “correction plan,” the university said that moving forward it would require all lab members to review protocols before conducting experiments.

Other kittens who suffered in 2021 included Luna — a 1-year-old cat, also known as M198411, who endured a punctured vein, low body temperatures, and a skull drilling — and Titan, an 11-week-old gray kitten who was “wobbly,” with muscle shakiness, low oxygen levels, a swollen face, and who ultimately had a seizure and suffered for at least 44 hours — or nearly two days — after a scan before researchers killed him, according to monitoring records.

Study protocol (Source: University of Minnesota, Emphasis: Lady Freethinker)

It’s Time For the University of Minnesota to Stop Killing Kittens

The University of Minnesota’s Minneapolis research facility had no reported animal welfare violations at its most recent USDA inspection on Aug. 29, 2022.

But it’s clear, from the university’s own records and the USDA’s official warning, that kittens suffered and prematurely died in these inhumane and deadly experiments — with no direct clinical applications for either humans or cats to date – despite more than $9 million of taxpayer-supported dollars and years of valuable research time.

The University of Minnesota told LFT that the newly created protocol — which required university medical staff to re-examine all procedures, including anesthesia, and put in place enhanced monitoring — was approved by the animal care use committee last spring but that, as of Jan. 10, researchers have “not chosen to resume this protocol or any other involving cats.”

It’s critical that these deadly experiments on kittens never resume — in any form.

Decades of peer-reviewed, gold standard research have pointed to irreconcilable genetic differences between humans and nonhuman animals that make experiments on animals costly, unreliable, and unsafe.

A growing number of studies also are highlighting the critical importance of studying the human brain and human afflictions using ethical, human biology-based alternatives to cruel experiments on animals.

Our world’s scientists are tasked to be innovators — not the defenders of ineffective, outdated, and dangerous experimental design that will continue to delay timely, safe, and cost-effective treatments for suffering humans.

It’s time for the University of Minnesota to officially and permanently end its deadly experiments on defenseless kittens and find a more compassionate way forward. Shifting away from tests on animals is the right choice for kittens and for suffering humans waiting for lifesaving scientific advancements and treatments.

If you haven’t already, please sign our petition urging the University of Minnesota to prioritize sending the surviving kittens to shelters or loving homes rather than killing them and to shut down their kitten experiments FOR GOOD. We’re also asking NIMH to withdraw support any additional support should these experiments resume, and for legislators to ask hard questions about why these deadly kitten studies started in the first place — and used taxpayer-dollars.

SIGN: Tell University of Minnesota to NEVER AGAIN Conduct Deadly Experiments on Kittens!