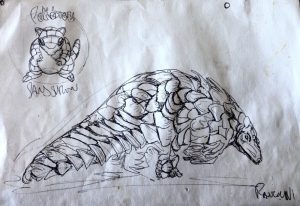

A walk through the Kruger National Park in South Africa and a chance stumbling across a Pokémon character started a 4-year-old Robbie Rorich on an artistic journey that would catapult him into lifelong passions — for nature, for wilderness, for people, and for cultivating a connection between them.

The image of Sandshrew — a tan and white armored creature with large dark eyes — captivated Rorich, who took pen to paper and created his first art as soon as he got home.

Years later, at age 26, Rorich — who was accompanied by his mother and a friend — passed near the same spot, where the small group was stunned to see a pangolin, a living embodiment of Sandshrew, ambling along the road.

“It was so unusual,” he told Lady Freethinker. “They are in the park but they are very shy. He stood right there in the grass for about 15 minutes. We had complete access to be with him — he was there, and we were there. It was another very clear message to make art. This time, it was sculpture, and this unfoldment came with a new way of being. The pangolin came and ripped out some cords in my mind, some negative thought patterns — just ate them in its own gentle way.

“It just blew me open — a very next-level gift that pangolins give us when we interact with them,” he added.

(Courtesy Robbie Rorich)

In May, the results of Rorich’s listening to that inner guidance were on display in Johannesburg and Pretoria, in an exhibit titled “Transcendence” that featured 33 sculptures of life-sized pangolins— some of the most exploited and trafficked animals in the world.

All eight pangolin species are protected under national and international laws, with two listed as critically endangered on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s Red List.

Rorich said the Transcendence collection curates pieces that speak to and for the earth — born from nature but also the necessity to “raise consciousness for our country’s creatures and our world’s hunger, spiritual and physical.”

“The collection centers around the story of the plight of Pangolin in Southern Africa and holds solace for many others — from aardvark to otter,” he said on Instagram. “With it, we hope to bring consciousness and information to you, and for it to transcend our differences and reach society, creating synergy between our wild and the wild, through gentle activism with fierce determination.”

Rorich has collaborated on exhibits with numerous other artists, including The Good Machine, and routinely donates half of his sales to causes. A previous, ocean-inspired collection benefited the Sea Change Project, which promotes and protects the Great African sea forest.

(Courtesy Robbie Rorich)

“The appreciation of the earth leads us to a really great place of looking after the earth and looking after each other,” he told The Daily Maverick. “I hope whoever walks into the exhibition space can really feel their connection to wildlife through the art in a space where people can connect to the life of these animals. We are all so interconnected.”

He added in an artist statement that his artwork is larger than he is.

“Through being present and allowing myself to open up to the subject of what I am sculpting, I feel that I am guided from start to end by a spiritual connection to my subject matter — be it a crocodile or a Goliath heron,” he wrote. “I am quite sure that it’s not just me who makes the sculptures.”

Rorich caught up with Lady Freethinker from Cairo, carving time out to talk about his artistic inspiration, his thoughts on co-existence and oneness, and why he counts nature as one of the “great teachers.” Answers have been edited lightly for length.

A Q&A with S. African Sculptor Robbie Rorich

Tell us more about your connection to nature.

I grew up in Johannesburg, about half an hour drive from the Kruger National Park. So often, on weekends and holidays, we would go and spend time in the wild. I saw elephants, lions, buffalo, giraffes — all the very visibly and immensely powerful animals. Over the years, I dove in deeper, loving the grasses and the sands and the spiders, the life and the web of nature that is in these wild places that we can go in and experience and be a part of. That comes with being born as a human; it’s part of who we are and what we need. I grew up with a clear understanding that an elephant is going to teach us as much as a school teacher, or a book, or a rock.

When did you start creating art?

I started drawing around age 4. I was walking in the Kruger Park and I found a Pokémon version of a pangolin on the ground. I was completely transfixed by this magical creature, and I went home and copied it on paper with a pen. It completely blew my mind, which I guess is what art is.

I started sculpting at school when I was 16; I fell in love with it the first time I touched the clay.

(Courtesy Robbie Rorich)

What is your artistic process like and what challenges have you brushed up against?

From the beginning, when I made art, I could feel that there’s a natural touch that wants to come through. It doesn’t need to be worked in an intellectual way; it just needs to be let free. We might be aiming toward something and thinking about something, but then we allow more to flow through us.

I’m definitely not there, but I know I am aiming toward letting that “free” in. I’ll get there soon. It’s obviously difficult when you’re an artist, trying to make money, and people like “this” and I’ve made art like “this” in the past. But this week, I got new clay, in Cairo, that I’ve never used before, and I am going to make some sculptures with that… so starting a new section now that might be truer to the true freedom of creation.

What really taught me to be receptive to what I want to sculpt was free diving under water – getting cold and getting close, which is a super fast way to lose your mind and experience a real closeness with nature and who we are, in a simple and often ecstatic way.

I set the intention to make art for people and then to be guided — to see things, to hear things, with what you might call our “inner ears.” Then we hear it shouting: “You know, it’s time to make me!” Often it comes in the form of a commission, someone saying, “Please make this for me.” (Inspiration also comes) from experiences of seeing the animals — of seeing a shyshark every time I dive until I make one, and then not seeing it anymore.

[It’s] not thinking about these things too much. Listening to the guidance. The pangolin walked up to us and said, “Hey, let’s make some art.” So not trying to be under any illusion that my opinions and thoughts are in any way near a more cohesive understanding than what is given to us by being open through learning from nature as one of the great teachers.

(Courtesy Robbie Rorich)

Tell us more about that — nature being a teacher.

A really nice way to think about that is the wild spaces and the wild animals on earth — they understand their oneness, and they’re not too caught up in their individuality, even though they are individual expressions of absolute beauty and the divine.

Humans hold on to our individuality, and don’t quite understand our oneness, although everything around us understands the oneness.

Do you think we can learn how to co-exist compassionately with the other beings here?

It’s not a question of are we going to understand it or not — we are. One day we will. Ultimately, Gaia will look after herself and us, with the help of God and Universal Love.

There may be times of fear, but it’s a purging of the fear that might need to be felt as it leaves the planet.

(Courtesy Robbie Rorich)

Why did you decide to couple your art with conservation causes and raising awareness about imperiled species?

In 2016, I took a year off from engineering to make art and run in the mountains. When I asked what I could make, I saw very clear images. It wasn’t too conscious. Ideas drop into people’s minds, and we can choose to follow through on them or not.

We are held by the Earth and by nature. Earth is our mother and provider in so many ways, and we can work with her to live here and grow together.

I don’t think it’s actually important, interestingly, to raise money for endangered species specifically. I think it’s important to curate a relationship between humans and nature, basically to allow humans to realize how much we are nature and how much we love nature, and how much nature and the world love us.

We’ve put differences between matter and spirit, but there is no difference: Spirit is in every atom. We’ve put differences between humans and nature, and there’s not. We have free will to act and do unnatural things, like put plastic in the ocean, but we are made of nature, of the elements, just like the leaves and the rocks and the lions.

How do you feel about the impact your exhibits have had so far?

I feel a deep reverence for this work of putting animals in bronze: that they’re going to be here for hundreds of years or more. I feel in my heart that the art I create has room to be seen more.

What’s next for you?

I just finished two sculptures of leopards. Next I likely will make a sculpture of a cat, for the owner of the guest house where we’re staying. Also lots of cycling and running.

(Courtesy Robbie Rorich)