If you asked arboreal adventurer Meg Lowman for advice, she might tell you, “Always carry a headlamp” or “Wear a vest with lots of pockets.”

She also might advise you to stop buying products containing palm oil, the demand for which is wiping out life-saving rainforests in Indonesia and Malaysia, or to start speaking up for the senior trees in your neighborhood facing a city-ordered chainsaw to make more room for roads or apartment buildings.

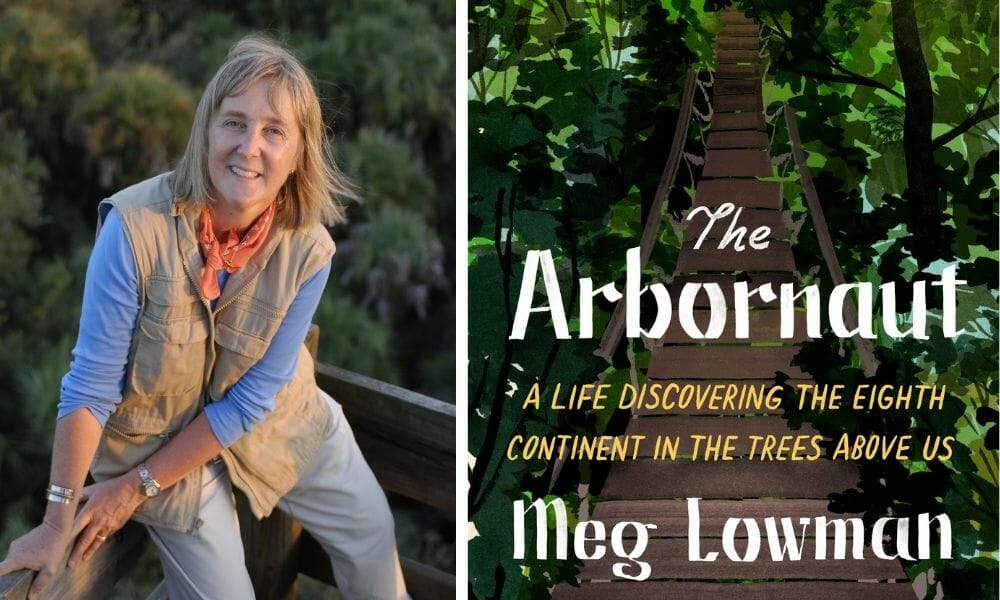

Lowman – an American biologist, educator, ecologist, professor, and executive director of the Tree Foundation – recounts her trailblazing work in canopy science and her escapades and challenges as a female scientist in her memoir The Arbornaut, released this year by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

Scientists now believe that more than 50 percent of the earth’s land-dwelling critters live in canopies unreachable for most humans – leading Lowman to dub the undiscovered forest heights the “eighth continent” and herself, as one of the first canopy climbers, as an “arbornaut.”

Lowman intersperses outlines of her scientific process and projects with engaging anecdotes – from her time spent camping out as a single female in remote areas of the Australian Outback to navigating negotiations with priests to save sole stands of trees surrounding Ethiopian forests, known as “church forests.”

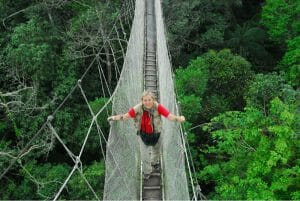

She details how she helped pioneer several canopy “walkways” around the world, where people without her climbing expertise can also experience the dazzling heights.

She also writes honestly about the challenges of balancing a time-consuming career that requires extensive travels with becoming a new wife, then the mother of two boys she raises to love nature as much as she does as a single mother.

Throughout the narrative, she underpins the value of trees – not only in their own right but also for human survival.

“In 2020, after tragic fires burned millions of acres in the Amazon, Australia, Indonesia, California and other landscapes, I was interviewed by the BBC,” she writes in The Arbornaut. “They only asked one question: What will happen if all the world’s forests disappear? My answer was simple but stark: People will not survive.”

She also emphasizes that other precious species also depend on healthy forests to survive.

“People are aware of endangered species, but not as aware of the clearing of their habitats,” she writes in The Arbornaut. “It is critical to save species, but that requires saving their habitat.”

Her goal in writing the memoir was to inspire people to learn more about forests and to save them.

“I hope my passion for these leafy giants will inspire readers to share a sense of wonder for our eighth continent, and maybe we can save it, together,” she writes in the book’s dedication.

Lowman spoke with Lady Freethinker about her pioneering exploration of forest canopies, overcoming challenges as a female scientist in a male-dominated field, and what people can do with their everyday purchasing power to make a difference. Answers have been edited for length.

For more information about Meg, check out her website here. For free resources including a map of the world’s canopy walkways, a rainforest-friendly purchasing guide, and action steps to help save the world’s forests — visit the Tree Foundation’s website here.

Meg Lowman on a canopy walkway (Photo Courtesy of TREE Foundation)

A Q&A with Meg Lowman, Author of The Arbornaut

Audio PlayerTell us more about your unique connection with forests and why you love them.

Forests are my best teachers. I found all of these amazing attributes out of the trees I studied, and I almost try to emulate trees as my role models. They give us a lot of examples about how we should live. Fancy being a tree; you can’t run away from your enemies. So they’ve developed these defenses. I just love the giant stinging trees in Australia; they are covered in physical and chemical stinging hairs. So if you didn’t get poisoned by the toxin, you got averted by the crazy physical burning sensation when you touched one of these leaves or stems. That was for me this wonderful lesson in life, especially as a naive girl in science. I thought, “I’ve got to get my armor, I’ve got to get more defenses. I have to figure out how to be smarter,” and the trees taught me a lot about that.

In your book, you speak to the challenges of being a female scientist in a male dominated field. What kept you going?

I think I just doggedly had a little pathway, and I was quietly pursuing that pathway. Overriding all the hurdles was this curiosity about leaves and trees; I just really had this passion for nature. I think all of us have those moments in our lives where we doggedly do what we do. You need to pursue it; you need to persevere.

How did your experience fuel your passion for inclusivity in the work you’ve done for women, minorities, and mobile-limited individuals?

My interest in inclusivity and bringing in minorities came from my own sense of being excluded. You learn the hard way. I remember so many times when I was on the out, or I was given the hardest job, or I was given no job, or the door was closed in front of me, and I thought, “Holy Cow, it really hurts.” So that gave me an extra passion for helping others. My empathy was pretty obvious, so I did tend to get a lot of the minority students as advisees when I taught college, and I tended to earn the trust of the priests in Ethiopia.

(Photo Courtesy of TREE Foundation)

Tell us about one of your favorite experiences of introducing others to trees.

One of my favorite experiences I talk about is a girl named Rebecca, who lost the use of both of her legs after a car accident and was one of our mobility-limited students. Not only did she excel in climbing trees and writing up publications about water bears, which was part of our summer research experience, but she dreamed of going to the Amazon. So I figured that out for her. I got my friends in the villages of Peru to retrofit an outhouse for her and a bed, and we even put a little platform on one of the canoes so she could roll her wheelchair into it. Sharing that kind of thing was just life changing for me, as it was for her. Those are the joys of being a scientist. Hopefully, we can allow all these different brain cells to come to the table. All of these diverse points of view are so important now.

Your book notes the conflict between the importance of trees and encroaching economic pressures and land development, while also showing that eco-tourism could be a more profitable and healthier alternative for both people and the planet. Can you speak more about that?

Trees are incredible. They give us fresh water. They control our climate. They give us medicines and building materials. They store carbon. They produce energy. They give us food. They are the most important genetic library on the planet. They conserve soil. And now we know they are this important spiritual place for about two billion people.

What’s amazing to me when I give talks at business schools or to corporate people is they have no idea; they never learned about the thing we call “natural capital” — in other words, the dollar value of a tree. It’s so enormous, but it never gets put in the accounting books. So people just think it’s some kind of decoration they can cut down whenever they want to expand a building or build a road. But in actual fact, we should treat them like these revered senior citizens in our communities and protect them, and worship them, and save them.

I think it’s important to understand the supply chain first. The indigenous people living in the villages, more often than not, sell their timber for very small dollars because they have no idea what its value is up in New York. Once it’s gone, they’ve taken all the nutrients; in rain forests, the nutrients are not in the soil, they’re actually in the tree itself. Usually the loggers burn the canopy bits that are left in big piles, so here are these poor villagers left with no soil, no livelihood, and yet everybody assumes they are the culprits. Really the culprits are a couple of the bigger corporate groups that farm these places and American consumers who don’t meaningfully try to destroy their children’s lives. But as we buy things that we don’t know where the products originated or as we purchase tropical products, we are contributing to that supply chain, and we are responsible for causing those farmers who are selling the beef and soy to have a market.

We need to feed and provide jobs for the people in the villages in the Amazon, but they are not becoming millionaires by cutting down their trees. In fact, they’re losing when they cut down their trees. So hopefully if we could offer them an alternate economic model, which would be eco-tourism, and encourage Americans to go down to Peru and go to places like India and Malaysia and Mozambique and see these gorgeous monkeys and trees and sloth, then we can support these people with an industry that’s not going to kill the planet and kill the rainforest ecosystem.

(Photo Courtesy of TREE Foundation)

What should people know about planting new trees, versus conserving old ones?

Nothing can replace these forests for our children and our grandchildren. We’re getting to the point where the planet is getting warmer and drier, and a lot of that is due to the deforestation process.

When we lose forests, we plant trees, which is a great thing, but it does not mean that we should stop trying to stand up for those old growth and big trees. Think about the poor koala bears in Australia, after all those fires. They can’t live in seedlings. They can’t even live in the canopy of a sapling. It will be well over a hundred years before those koalas will have anywhere to go. So essentially even keeping the koalas alive in the vet hospital will not help them because they will not be alive when those trees grow back from seedlings. We have this crazy impatience as humans to think that we can substitute a sapling for a big tree. We have to think about the timeline of a tree, which is very slow growing for the most part.

Obviously we have not detected the millions and millions of species that live up there, nor have we classified them. And all of a sudden we are losing forests, so of course we are losing a lot of that biodiversity before we can lay eyes on it, before we can understand its importance or value. It’s pretty scary.

There are so many layers of life up there. If you do clearcut a forest, how will you get back all those orchids, all those bromeliads, and all those amazing vines? It takes more than a thousand years; it also takes a great big level of chance. We are really and truly fooling ourselves to think that replanting is easy as a solution to deforestation. We just need to save big trees, and that in turn saves all these cool creatures on the planet that we really need for our own crop pollination, for our own soil turnover, for our own different functions that keep us healthy and alive, too.

How do you feel about the future for the world’s forests?

In all fairness, I’m very worried. I’m not as optimistic as I wish I could be. My one and only hope is the young people of today, if they can be smarter and more innovative than my generation was and come up with good solutions. I hope and pray that we give them the resources and the tools so that they can be better and smarter than I ever was. So much is weighing on their ability to come into this world and make a difference.

[From the Arbornaut]: My children tease me to switch titles from arbornaut to arbornut, because the world of forest conservation is so downright depressing and riotous. I do know the world needs more citizen scientists to marvel at the workings of forest ecosystems, more communities to save big trees as their most venerable residents, more arbornauts to share their expertise in under-explored places, and more inclusivity of all the diverse voices calling for conservation. If I’m right, with hard work, a whole lot of luck, and a willingness to believe that we’re all in this together, one arbornut can seed a forest of citizen scientists ready to stand tall for their beloved trees.

Meg Lowman rappelling down a tree (Photo Courtesy of TREE Foundation)

5 Steps You Can Take Today To Help Save Rainforests

- Buy products that don’t contribute to deforestation. Look for labels certifying products haven’t harmed the rainforest, including the badges for the Rainforest Alliance, the Forest Stewardship Council, and the Sustainable Forestry Initiative. If you’re a coffee drinker, search for labels that note the crops are “shade grown” – under the forest canopy, rather than out in the open of clear-cut land. Avoid timber originating in tropical countries like Brazil or Peru. Avoid products containing palm oil – from margarines to shampoos – “oil palm,” or its numerous other names. Also consider avoiding tropical fruits, like pineapples or bananas, and stock up on locally sourced fruits and veggies through co-ops or farmer’s markets.

- Ask your grocery stores – and your legislators – to better label countries of origin and supply chains. It’s hard for consumers to make conscientious choices given the dearth of labeling requirements in the United States, Lowman said. She encourages people to politely “make a fuss” with local grocery store managers about more transparently sourcing their products and with legislators about demanding that products clearly label the energy footprint and geographical origin.

- Join a citizen science program or a climate change solution group near you. Lowman recommends programs like Earthwatch, which allow everyday people to connect with scientists in need of additional hands and eyes to conduct their research. Groups like 350.org, the People’s Climate Movement, or the Sunrise Movement also can jumpstart your introduction into the pressing environmental issues of our times.

- Advocate for Trees and get outside. If your city or county plans on cutting down old trees in your community for malls, buildings, or road construction, learn all you can and then speak up. Also get outside: visit forests often and share your love of trees with others.

- Eat Plant-Based. Animals raised for slaughter in the dairy and meat industries pack an outsized environmental impact, and their waste is a major source of greenhouse gas emissions, the Tree Foundation notes on its website.