More than three years after multi-million dollar experiments on intentionally brain-damaged monkeys raised a collective congressional call of “grave concerns,” the experiments have continued – with scientists routinely creating lesions in some macaques’ brains while severing parts of others’.

There’s still no immediately applicable human health benefit, more than 20 years after the studies started.

And the cruel experiments have continued to cost the federal government – and taxpayers– millions of dollars, according to documents obtained from the National Institutes of Health.

In 2018, nonprofit White Coat Waste exposed videos and documents, obtained via Freedom of Information requests, related to brain-damaged monkeys being exposed to fake rubber snakes and spiders to study their fear response – experiments that had cost taxpayers over $16 million.

In response, Congressional leaders, led by Rep. Brendan Boyle (D-PA), demanded answers from the National Institutes of Mental Health (NIMH) – including what studies were being conducted on monkeys, the number of animals used, what happened to them at the experiments’ ends, and how their suffering had been applied to producing human treatments.

Months later, NIMH responded with a brief 4-page letter, which Lady Freethinker obtained via FOI request, which revealed that the three studies responsive to the legislators’ request had cost more than $46 million, had involved more than 140 monkeys (none of whom were sent to sanctuaries), and had not yielded any “return on investment” – meaning a direct benefit for people.

Documents related to the three identified studies also show that they’ve continued – despite voiced Congressional concerns – and cost an additional $8,353,174 from 2018 through 2020, according to NIH RePORTER, the NIH’s online database of scientific projects.

Boyle, who spoke with Lady Freethinker via email, said the NIMH’s response to the situation and the results of the experiments have been alarming.

“My colleagues and I appreciate NIMH’s response but were alarmed by the details,” he said. “These ongoing psychological experiments on monkeys have gone on for over 25 years, cost Americans millions of public dollars, and apparently have not led to treatments for human patients.”

“The return on investment for taxpayers have been abysmal,” he added.

Justin Goodman, WCW’s vice president for advocacy and public policy, said the NIMH response “confirmed that the waste and abuse [at the facility] is even worse than we previously thought.”

“According to the letter, over $46 million of taxpayers’ money has been squandered to give monkeys brain damage and scare them with fake snakes in spiders in wasteful experiments that have done nothing to improve human health since they started in 1996,” he said.

The National Institutes of Mental Health did not respond for this story, despite multiple outreach efforts over two weeks.

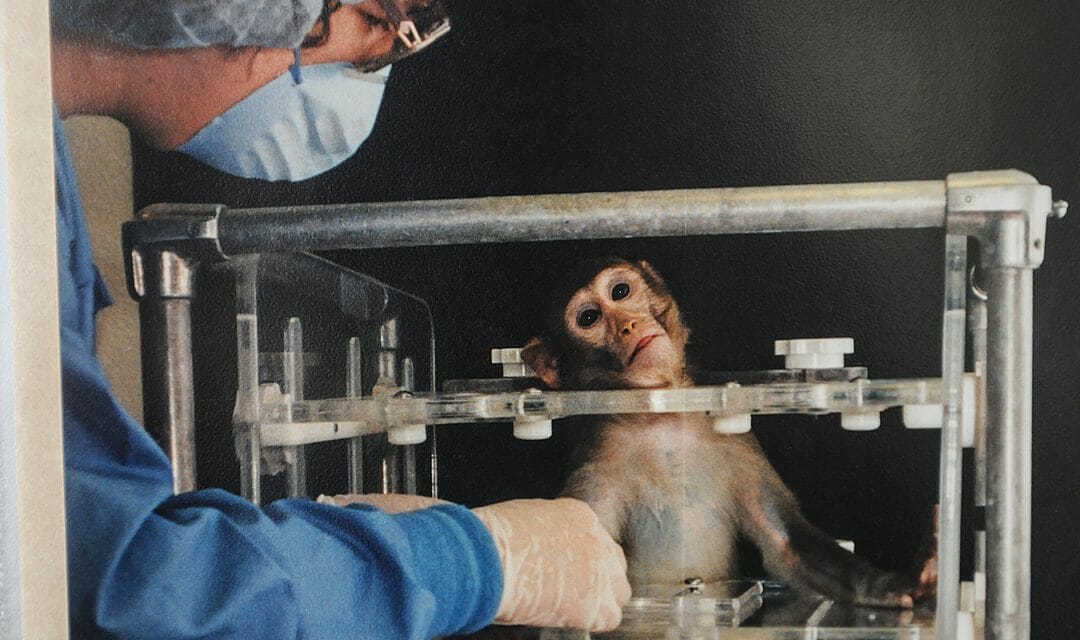

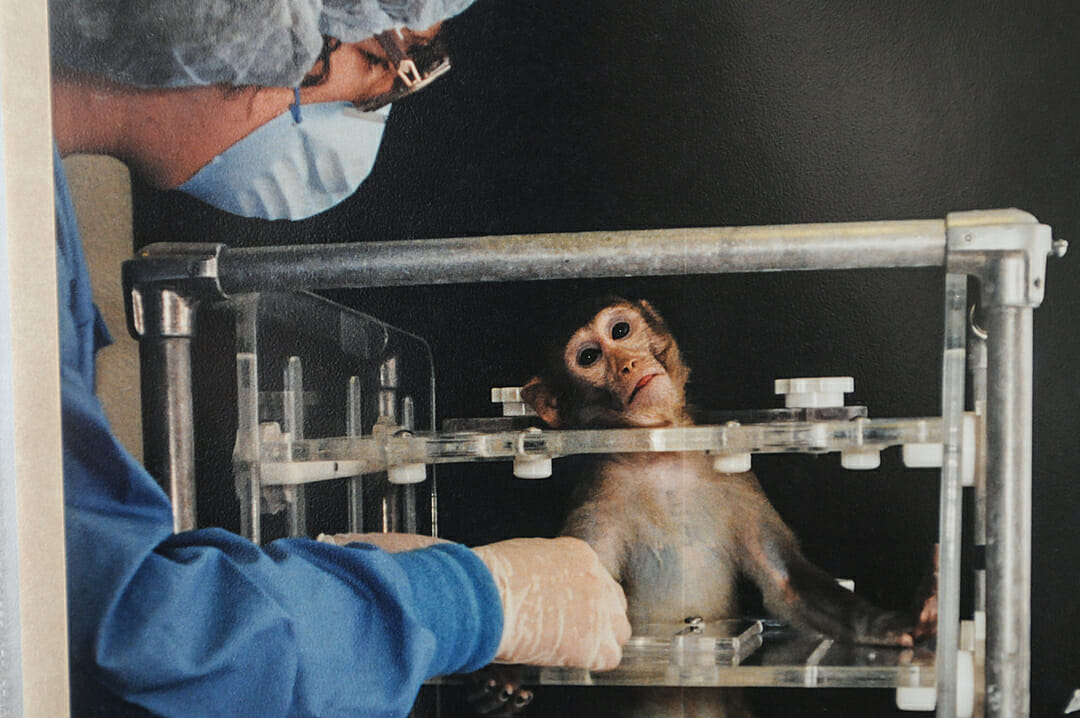

Representative Image via Adobe Stock

Grave Cause for Concern Over Taxpayer-Funded Experiments on Monkeys’ Brains

In February 2018, Boyle – along with Reps. Brian Mast (R-FL), Lucille Roybal-Allard (D-CA), Matt Gaetz (R-FL), and Dina Titus (D-NV) – sent a letter to the federal government asking for information on monkey testing.

The request followed video footage exposed by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and documentation from nonprofit White Coat Waste (WCW), which highlighted the fear-based experiments on a reported 149 monkeys – 60 of whom were purchased “new” and the rest of whom were obtained through a “recycling” program, in which animals endure other experiments before being used in additional ones, according to The Hill.

That documentation showed scientists had literally burned the brains of monkeys with acid, then confined them to barren metal boxes and exposed them to replicas of snakes and spiders, according to WCW.

The legislators’ letter referred to experiments that had cost more than $16 million since 2017 and which had involved “damage on monkey’s brains with acid, suction or burns, chain them up in tiny cages, and video record them being frightened with mechanical snakes, and, as the researchers state, ‘hairy rubber spiders’” – as well as research “where monkeys were given brain damage and tested on whether they could tell the difference between monkeys’ faces and pieces of fruit.”

The legislators asked for a list of all active grants supporting monkey-based research in NIMH, how many years each project was funded, how much taxpayer money was used, the “return on investment” – i.e., direct application of the studies to treating human disease or illness – and the total cost over time.

Despite the NIMH’s assertions at the time that the experiments were being conducted to gain insights about human disorders, including anxiety and depression, the legislators’ letter also noted that a clinical psychologist interviewed had said the tests “will not translate to improved outcomes for the real human patients.”

The 4-page response – signed by NIMH Director Joshua Gordon and sent to legislators months later on April 21, 2020 – confirmed that assertion when the department sidestepped the return-on-investment question – saying, instead of specifics, that “the biomedical research community uses a variety of different measures to assess” a study’s success.

Gordon added that any scientific advancement involving animal testing could take decades for suffering people to see any practical results.

“An individual basic science research program’s contributions cannot be fully appreciated in terms of specific changes in clinical practice or specific impacts on the economy directly attributable to that specific program,” he said. “The development of a new therapeutic drug or treatment strategy is almost always built on years or decades of basic and translational research from many different laboratories.”

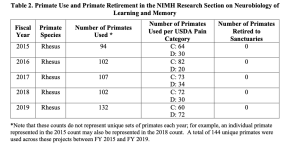

The federal agency went on to mention three projects from the NIMH Research Section on Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, between 2015 and 2019, that had collectively cost more than $46 million and used 144 monkeys – including an undisclosed number who endured multiple procedures across those years.

Each year, more than 60 monkeys were involved in “Class C” experiments – classified by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) as experiments where no pain and no pain drugs were involved.

The number of monkeys involved each year in “Class D” experiments – classified by the USDA as procedures involving pain, to the level where pain relievers were supposed to be delivered – ranged from 20 monkeys to 72 monkeys.

Pain categories and number of monkeys involved (Courtesy NIMH)

None of the primates were retired to sanctuaries, according to the NIMH letter.

The purpose of the experiments (and the umbrella research section) was to improve understanding “of how the brain responds to fear, which will support future efforts to develop treatments for mental illnesses, including specific phobias and PTSD,” the agency wrote.

A read-through of the studies, all overseen by lead project manager Elisabeth Murray, shows that scientists’ plan to study human-specific learning, memory, mental illnesses and disorders involved slicing parts of monkeys’ brains or creating lesions on different parts of their brains, then having monkeys complete tasks like pointing to images on a computer screen.

Continuing Cruel Experiments on Monkeys and No Direct Human Benefit

The NIMH report to Congress identified three studies that have continued through at least 2020, according to NIH RePORTER.

For each study, there is no data available on the RePORTER’s form regarding a “public health relevance statement,” although the NIH Funding Categories for the experiments include “brain disorders,” “major depressive disorder,” “anxiety disorders” and related tags.

Since 2018, close to $2 million has been pumped into experiment ZIA-MH-002736 (also known as “Neural Substrates of Stimulus Recognition and Association Memory”) — an experiment that aims in part to look at the human ability to learn through our lifetimes by studying monkey brains.

Over the years, as part of this experiment — which has been funded since 1996 — monkeys have had holes drilled in their skulls during “cerebral ablations” and been given lesions on their brains via “bilateral excitotoxic amygdala damage” as well as damage to their hippocampus.

The experiments to date have concluded that prolonged learning can impact the white matter microstructure of the brain, although as of 2018 — more than 20 years after the start of the experiment — the researchers noted “additional subjects are required to draw firm conclusions regarding the relationships between changes in white matter and learning.”

The most recent filings for the experiments also note that monkeys who were trained to reach out and touch an object on a computer screen, then in a second test touch an object in the computer screen’s foreground despite multiple geometric shapes also on the screen, displayed “wide individual variability in their ability to learn the different tasks.”

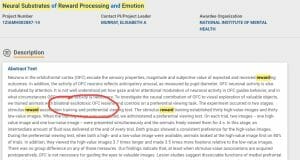

The second study (identified in the NIMH report as ZIA-MH-002886, or “Neural Mechanisms of Reward Processing and Emotion”) has cost an additional $1,982,393 since 2018 to study decision making in monkey brains.

This study also involved creating lesions on monkeys’ brains, with 2020 filings noting that brain-damaging monkeys increased their heart rates while decreasing their reaction times. The experiments also have looked at how a monkey’s taste preferences may impact their decision making, and whether monkeys could learn to differentiate between images that researchers assigned “high” or “low” values, which they transmitted to the monkeys by giving them varying levels of water as a “reward.”

One reference to the multiple experiments involving inflicting brain lesions on monkeys (Source: NIH RePORTER

The third study (ZIA-MH-002887, also known as “Neural Substrates of Reward Processing and Emotion) netted almost $1.3 million in 2020 alone for scientists to take monkeys inflicted with lesions on their brains and see if they could get them to look specifically to an image that the scientists assigned “high” value, versus other images they assigned “low” value.

These studies also involved surgically severing parts of the monkeys’ brains — namely, disconnecting the prelimbic cortex or the orbitofrontal cortex from the amygdala, commonly associated with a being’s fear response — for a finding that each part had its own role to play in monkeys’ storing and processing of information.

Procedures in this experiment during 2018 involved the fake snakes and spiders that drew Congressional and public concern, according to NIH RePORTER.

Congressional and Public Response Following WCW Exposé

Goodman said that following the NIH’s “unsatisfactory” response to Congress, and the lack of action to end the experiments, WCW worked with Roybal-Allard to include language in the federal agency’s 2021 spending bill.

That language requested an independent review of all intramural NIH primate experimentation by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM).

NASEM is putting together a review committee, Goodman said. He’s hopeful.

“Previous NASEM reviews of taxpayer funded experiments on other animals, including chimpanzees and dogs, have found much of it to be unnecessary and prompted the end of many cruel and wasteful projects,” he said.

The added language emphasizes the obligation in federal law to minimize animal research and consider the use of alternatives to animal testing whenever possible.

The NASEM review will include a dive into existing and anticipated future alternatives to forcing monkeys to suffer cruel procedures, and how NIH can reduce their current reliance on nonhuman primates for their experiments.

In addition to there being no immediate results related to treating human illnesses, Boyle said another remaining concern for him — as a steward of constituent and taxpayer dollars — is that scientists have to inflict artificial conditions onto the animals used in the ongoing experiments.

“Artificially inducing diseases in animals confined in labs is a poor way to study human illnesses, which is why many drugs and treatments developed using animals fail in people,” he said.

That’s a reference to evidence, established for decades and growing, that more than 90 percent of drugs that pass safety tests on animals end up never reaching human markets, after clinical trials show they are ineffective or dangerous for humans.

“Science has advanced leaps and bounds in the quarter century since government led psychological experiments on primates began in 1996,” Boyle continued. “There are now more humane and effective methods for studying the human brain. We can and must do better than outdated animal experiments.”